While I was an undergraduate music student at college, I did a lot of ear training.

We had 3 ear training lessons a week (60 minutes each) and there would be an exam every few weeks.

By the time I was at university, I had already trained my ear to a high level, so ear training tests were very enjoyable – something I actually looked forward to (no exaggeration). But I also remember taking ear training tests before training my ear – and I remember these being the scariest type of test that could ever be invented.

So in this post I share my top 8 tips to dominate ear training tests – enjoy!

The ‘Standard’ Ear Training Test

Most ear training tests go like this:

– The teacher plays a piece of music – at the piano, or from a recording.

– The music is played 5 times, with a minute’s pause between each playing.

– Students sit at desks, in silence, away from any instrument.

– All you’re told is which key the music is in – e.g. ‘This piece is in F minor’ – and you have to figure out the melody notes and maybe chords by ear.

– You write down your answer on manuscript paper, and hand it in.

So here’s how I recommend you approach a test like this:

#1. Internalize the music

Don’t start coming up with theories right away. The first 1-2 playings should be spent listening only, and memorizing how the music sounds.

You need to be able to replay the music in your mind, during the rest time between playings. That way you’re not relying entirely on the instructor’s playing.

You can sing things back in your mind, and slow everything down.

So just relax in the beginning, and listen.

#2. Do the work during rest periods

Most of the ‘transcribing work’ should be done in the rest period between playings – when the music isn’t being played.

I suggest that you come up with a theory during the first or second rest period – and then use the next playing to test your theory – does it sound right? Does it hold up?

If not – use the next rest period to come up with a new theory. And then test that theory during the next playing.

Does it sound right? Does it hold up?

If not – then do the same again – come up with a new theory.

And hopefully by the final playing, you have something that holds up – which can only be the right answer. After all, if you’ve been told what key the music is in (e.g. ‘F minor’), then there’s only 7 notes the melody can be – so each wrong answer is one less place to look. Ear training is largely a process of elimination.

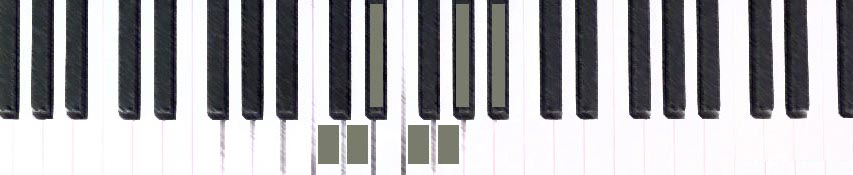

#3. Intervals first

There’s many ways you can transcribe music by ear – but the most appropriate technique I suggest for high school / university tests would be this:

Take a section of the melody (usually the beginning) and identify several intervals in a row.

You don’t have to worry about note names yet – just figure out a few of the intervals alone – like this:

‘ascending 5th’ – ‘descending whole-step’ – ‘ascending minor 3rd’

You don’t have to identify every interval in the entire melody – just 3 or 4 in a row will probably be enough.

How do you identify intervals by ear?

Many teachers will tell you to use ‘musical association’ – e.g. use the ‘lullaby’ melody to recall the minor 3rd, or the ‘bridal march’ melody to recall the 4th, etc.

But I don’t think this works very well. It’s hard to recall an unrelated melody while listening to music, and feels pretty unnatural to do. I’ve never used musical association to identify intervals, and I’m pretty sure no great musician ever did either.

What do I suggest instead?

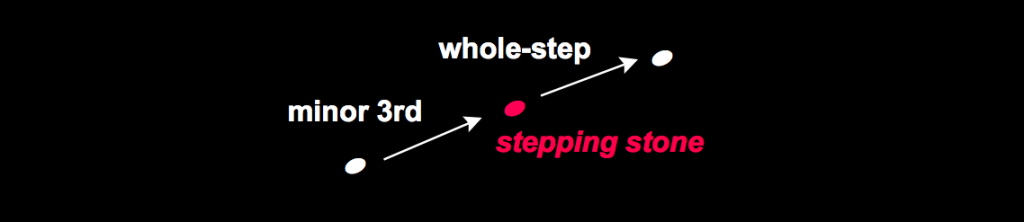

When you’re not sure what interval you’re hearing – here’s what I do:

Sing back the 2 notes repeatedly (e.g. C – F – C – F).

Now break up the interval, by singing an in-between note (e.g. C – Eb – F).

Can you identify the 2 smaller intervals that make up the whole? If so, then add these 2 together:

minor 3rd + whole-step = 4th

Lets take another example – say you’re singing back an interval – bottom note – top note – bottom note – top note. You don’t know what it is, so you adding an in-between note. You sing up a whole-step (from the bottom note).

Now, how much further do you have to sing up to hit the top note? You try it, and you find yourself singing another whole-step.

So you’ve broken the interval into 2 whole-steps – which means that the interval is a major 3rd (whole-step + whole-step).

So you can use this ‘stepping stone’ method to identify 3 or 4 intervals in a row.

#4. Where do the intervals fit?

Once you have 3 or 4 intervals in a row figured out, now you can start thinking about where the melody fits within the scale – so that you can assign note names – like ‘F’, ‘Ab’, ‘C’, etc – rather than just having intervals floating in space.

For any interval you hear in a melody, there’s only so many places that interval can be found within the scale.

So if you’ve been told ‘this piece is in C minor‘ – and you hear a half-step in the melody – well there’s only 2 places that a half-step can exist within the 7 notes of C minor:

D – Eb or G – Ab

And straight away you can narrow your melody’s possible location to these 2 places.

Or if you heard a major 3rd in the melody, then there’s only 3 places in C minor scale that a major 3rd exists:

Eb – G or Ab – C or Bb – D

You’re scanning the scale to see where the intervals fit, and eliminating all the places it can’t be. And the more intervals in a row you can identify, the more you can narrow down your options.

For example – there might be 3 places a major 3rd can be – but there’s only one place a major 3rd + a whole-step can be (Ab – C – D).

#5. Humming

Usually students are required to transcribe in silence – without singing out loud. This goes against the normal way someone would transcribe, in real life (it’s natural for musicians to sing). The only reason students are told to transcribe in silence is so as not to distract other students.

However it’s still possible to hum quietly to yourself without disturbing others:

Plug one of your ears with your finger, and hum very quietly.

You’ll find that you can hear yourself clearly, while no one else can.

#6. Think logically

When you scan the scale for places the intervals could fit, you’ll often be left with 2 possible places that you have to decide between.

But ear training is about ‘logical thinking’ – learning the norms of music.

For example:

– It’s quite common for a melody to start on the root of the scale (so if you’ve been told that the music is in C minor, it’s reasonable to guess that the melody might start on C).

– Following the root, the 2nd most likely starting note would be the 5th of the scale (in C minor, that would be G).

– It’s also likely that a melody will end on the root, or maybe the 5th (you can always work backwards to figure out the notes preceding the end note).

So once you’ve identified the few places the intervals COULD fit, use a bit of logic (the points above) to narrow your search down to one ‘most likely answer’. And then use the repeat playings to continue to test your theory – does it sound right? Does it hold up?

#7. Track the melody

Once you know where the melody is within the key, transcribing becomes easy. Even if you just know where a 3 note series is (the 3 intervals you identified, and located within the scale), it is fairly straightforward to keep track of the melody wherever it moves from then on.

You no longer need to figure out intervals with accuracy – you can hear when the melody runs up in step, and you don’t have to get bogged down with whether it was a ‘half-step or a whole-step?’. You know where it is within the scale, so your knowledge of the scale tells you what the surrounding notes are.

And a lot of music will move a lot by step – so it’s not like you’ll have to identify a lot of big leaps.

It’s also good to know that most melodies never jump beyond a 5th – so really you’ll only be dealing with about 6 intervals most of the time:

half-step, whole-step, minor 3rd, major 3rd, 4th, 5th

#8. Switch the key

What if you’ve tried the steps above, but it’s still not working?

When I was in ear training exams, the instructor always told us what key the music was in – ‘E minor’ for example. However, sometimes this only turned out to be a huge distraction. I’d try coming up with my transcription in E minor, and it just wasn’t clicking.

But then I’d say to myself – ‘lets just listen to it as though it’s in C minor’ – which was my favorite key that I played in best – and suddenly it clicked during the next play through.

Just by changing the key in my mind, I could hear every note and chord from one play through.

And then I’d transpose everything back into the music’s actual key (in this example, just transpose each note up a major 3rd, which you can easily do at the end of the test).

So sometimes, thinking about the music in a different key is all it takes to unlock the music. I still do this to this day – sometimes I listen to a song and the notes aren’t coming to me automatically like they usually do – so I switch the key in my mind, and then it clicks.

Further Training

If you’d like to see this process in action, you can watch my new ear training video series by clicking the image below.

This is 4 of my best and most important videos showing you how to play music by ear.

This series is completely free, but will only be running for a limited time. To sign up just click the image below:

Thank you for reading, and I’ll see you in the next post!

– Julian Bradley, MA music